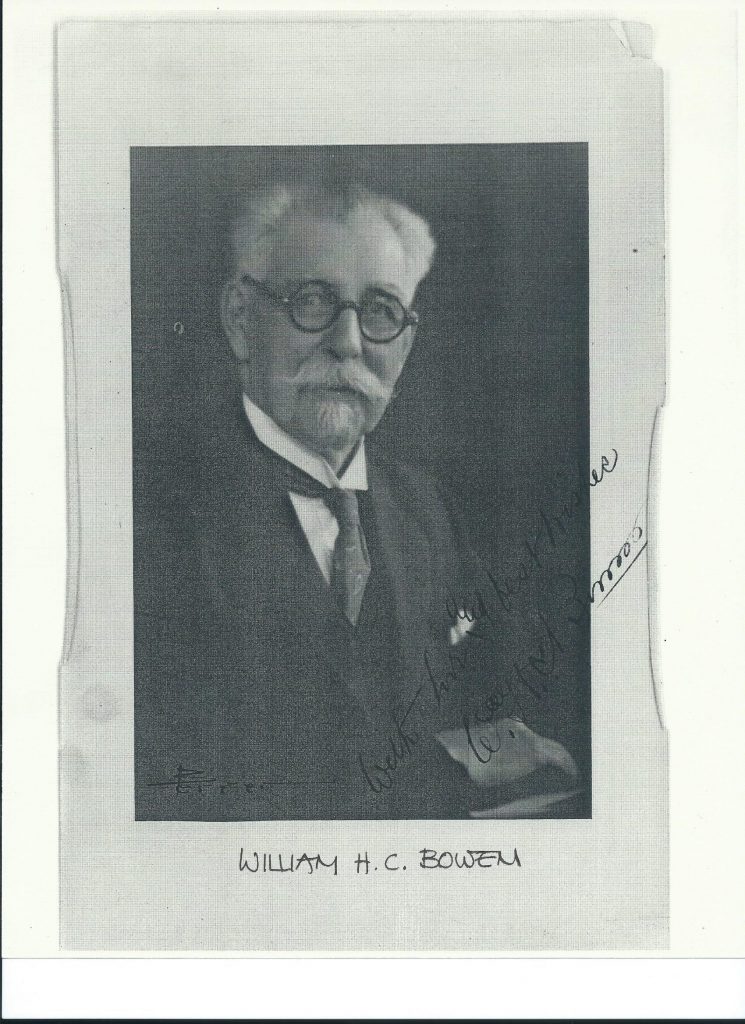

The following is the story about how Col. William (Willie) Holman Cary Bowen, once a “grasshopper clerk,” became an Army officer. It’s an excerpt from an interview in 1927, when Willie was 75. He died five years later.

I was born at Old Fort Union, NM, January 7, 1852. My father, Captain Isaac Bowen, was the tenth child in a family of twelve children. His father, Jonathan Bowen, was born in 1782, as was his mother, whose maiden name was Vashti Wheeler. Father was born November 29, 1821, and graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in the Class of 1842. After receiving his commission as a Second Lieutenant, he was assigned to the artillery branch of the service and sent to Fort Kent, Maine, and then to Hancock Barracks at Houlton, Maine. My father met and married my mother at Houlton. Not long after his marriage, my father was ordered to join General Zachary Taylor’s army for duty in Southern Texas and Northern Mexico. This was in 1846. This is where he met and was associated with Ulysses S. Grant of the Fourth Infantry who was on duty in Taylor’s army. Before long the Fourth Infantry was made part of General Scott’s, and Lieutenant Grant left with his company, while father remained in Northern Mexico.

In 1851, General Sumner was sent to Santa Fe to take over part of the territory which Mexico had ceded to the United States. My father, now a captain, was Chief Commissary of Subsistence and went with General Sumner as supply officer. My mother went with father to Fort Union. The first army post established in the new territory was Fort Union, and there I was born. When I was three years old, father was assigned to a station at New Orleans. I don’t think they wanted to go there.

In October 1858, father and mother died within a few days of each other of yellow fever. There were four of us children, but the baby died too. We were left in the charge of Margaret, a Negro slave, and, by the by, she took excellent care of us. Within a few months, my father’s brother, Dennis Bowen, came down to New Orleans and took us children back with him to his home at Buffalo, NY. Margaret came too.

When I was 18, I went to mother’s old home in Houlton and clerked in a store for two years, after which I went into the law office of Llewellyn Powers, later governor of Maine. I read law with him for two years, but was not admitted to the bar for some years later.

In the summer of 1874, I struck out to see the world. The fall of 1874 found me in Omaha, Nebraska. Many of the homesteaders in Kansas, Nebraska and Iowa were starved out in the summer of 1875 by a plague of grasshoppers that ate up every living thing. Congress voted money to purchase food for the grasshopper sufferers. The fund was administered by the supply officers located in Omaha. The younger officers of the department were detailed to make lists of the farmers needing help. From these lists ration returns were prepared and as this involved much additional clerical work, civilian clerks were employed. We had no such things as carbon copies in those days and the lists had to be made in quadruplicate. My appointment as a “grasshopper clerk” was a temporary one, but I secured the appointment in a rather peculiar way. An officer brought a list to me at 4 o’clock in the afternoon. There were 20 pages of names. He wanted the list by 9 o’clock next morning. I had to make not only the original, but three handwritten copies of this list and also to figure the amount of rations due to each family. I turned in the list at 8:30 next morning and when it was checked over, it was found there was not a single mistake.

I became acquainted with General George Crook, department commander, and his staff, as well as the younger officers. When they learned that I was the son of an officer of the Old Army who had died prior to the Civil War, they urged me to try for a commission. General Crook advised me to go back to Washington to see President Grant and ask if I could not secure a commission from civil life. In those days, after the West Point graduates were provided for, there were frequently some vacancies as second lieutenant, so that appointments were made from civil life. When all of the graduates of the class of 1875 had been given commissions as second lieutenants, it was found that there were still 14 vacancies.

Senator Hamlin of Maine, a boyhood friend of my mother’s, signed my application for one of those vacancies. The application was also signed by Senator Morrill, Representative James G. Blaine, Eugene Hale and others. When I reached Washington, I found that President Grant was at his summer cottage at Long Branch, NJ. It had taken practically all my money to make the trip to Washington and I put up at a cheap hotel. The next morning I made the two-mile walk to the President’s cottage. After a long wait, I finally secured an interview with the President’s secretary. Fortunately for me, he was an army officer, and when he learned that my father had been an old-time army officer, he told me he would arrange an interview for me.

He told me to come at 11 o’clock, two days later, and to be sure to be exactly on time. I didn’t have money enough to hire a hack, so I borrowed an umbrella and made the two-mile walk through the wind-driven rain. I was shown to a porch overlooking the ocean, where a few moments later President Grant joined me. He was very affable, shook hands, and said to me, “Are you by any possibility related to my old friend, Lieutenant Isaac Bowen?” I said, “I am his son.” He seated himself in a wicker settee and motioned for me to sit down beside him, and as a result of this interview, I secured my appointment as a second lieutenant in the United States army.