Kia ora is a Māori language greeting which has entered New Zealand English. The name is a common greeting in the Māori language and literally means “be well/healthy” or “may you live” and is translated as an informal “hi” at the Māori Language Commission website Kōrero Māori. The New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage website NZ History lists it as one of 100 Māori words every New Zealander should know, with a definition “Hi!, G’day!”. It also signifies agreement with a speaker at a meeting, as part of a culture which prizes oratory (and maybe blog posts?) as infotainment.

Kia Ora, New Zealand, is also a location, which is now a small dairy farming locality near Auckland. This is where my parents, Gertrude Ruth Munsell and Clarence Harry Haug, were married on July 4, 1944. Everyone in the military was leaving New Zealand by mid-1944 and the newlyweds were separated after their whirlwind courtship and romantic marriage ceremony. By late-1945, they were reunited in the US as shown in these photos taken at Warner Hot Springs, California, on their delayed honeymoon.

Gertrude Ruth Munsell and the American Red Cross

Once the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred on December 7, 1941, the American Red Cross (ARC) rapidly mobilized in order to fulfill the mandate of its 1905 congressional charter requiring that they supply voluntary aid to the sick and wounded of armies in time of war and to serve as a source of communication between the civilians of the United States and their military. The War Department decreed that the Red Cross would be the only civilian service organization permitted to work with overseas military personnel. Realizing that building and maintaining troop morale was an important component of victory, military leaders and the War Department assigned much of the responsibility for morale of the troops to the ARC, beginning during the early phases of troop buildup. Stateside, civilians volunteered to work in canteens and at transportation hubs, providing food and entertainment to the GIs who were in training or travelling. As servicemen started to go overseas, the need for paid staff and volunteers escalated and the Red Cross created a sophisticated campaign to recruit women to serve in this role.

The American Red Cross had very high standards for their female staff and volunteers – standards which were higher than those of the military. Applicants had to be college graduates, at least 25 years of age, have stellar reference letters, pass physical examinations, and have an outstanding personality as demonstrated at personal interviews. With the rigorous selection process, only one in six applicants made the cut.

Once accepted, the new staff and volunteers were sent to Washington, D.C. to the American Red Cross training program located on the campus of American University. There they received multiple immunizations, were fitted for Red Cross uniforms, and underwent several weeks of basic training in the history, policies and procedures of the ARC and the American military. There was considerable attention given to the appropriate way to wear the uniform, with ten pages of specific instructions in the Red Cross uniform manual – collars always to be pinned, no earrings, hair ornaments, “brilliant nail polish” or “excessive use of cosmetics.” After basic training, some recruits received additional training in programs emphasizing such things as recreation or administration. Once training was completed, the volunteers worked locally while awaiting their overseas orders.

My mother, Gertrude Ruth Munsell, was supremely qualified to be in ARC administration. By 1938, she had obtained an MA in Public Administration from the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, MN. Now going by her middle name, Ruth Munsell had worked for the Works Progress Administration (public relief, caseworker supervisor) in Jefferson City, MO, for several years after obtaining her BS in Public Administration from the University of Missouri in 1931, and then took a leave of absence to accept a fellowship for her advanced degree. Afterwards, Ruth moved back to Missouri and worked for the State Social Security Administration (district supervisor) in Jefferson City. Her family was nearby in Hannibal, MO, where her father worked as a rubber plant engineer for the International Shoe Company. In 1940, her mother died unexpectedly and her father died of a heart attack two years later. Ruth’s her younger two sisters had left home, so it was a good time for a single woman to heed the wartime call.

Grieving for the loss of her parents within two years of each other, Ruth was likely recruited by the American Red Cross in Missouri and traveled to Washington, DC, for training. She was 34, single, a college graduate, attractive, and had a pleasant personality – just what the ARC was looking for. By 1943, she had her overseas orders and was transported to New Zealand to manage a series of Red Cross Clubs.

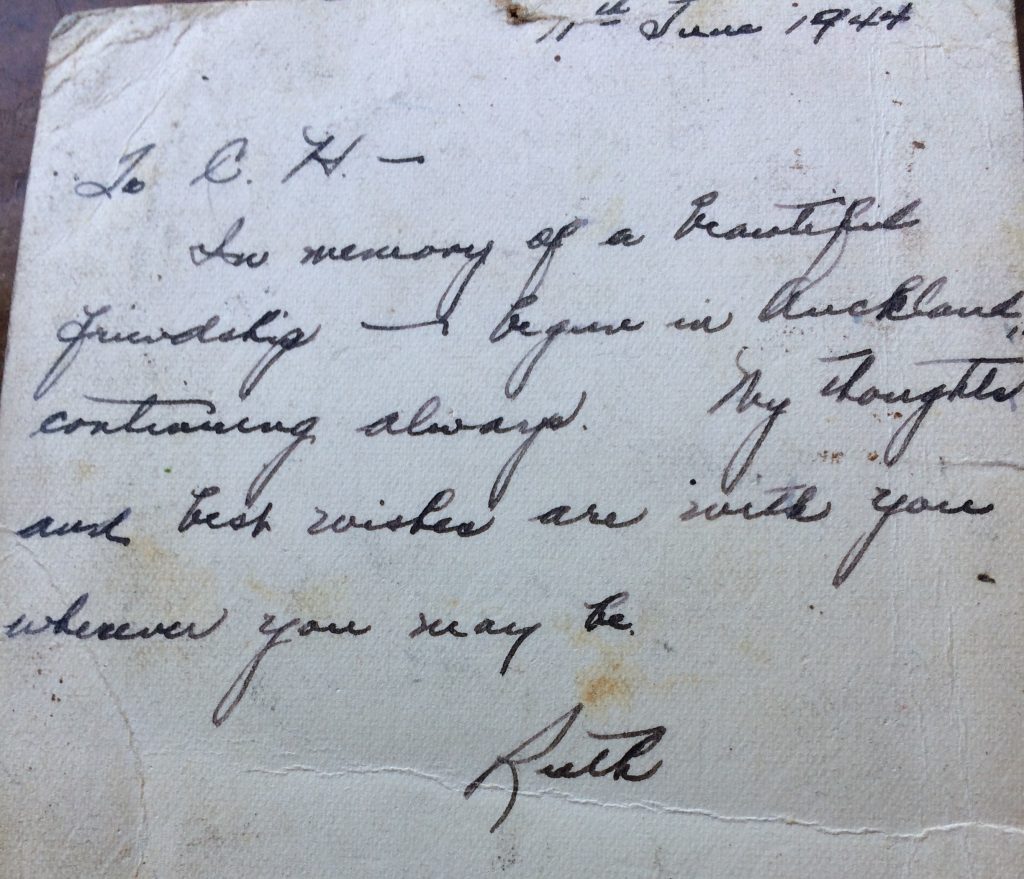

Based on a news report of her marriage, she worked as director of an ARC Club in Wellington called the Cecil Club, worked in a similar capacity in Masterton, and then at a club in Auckland, where she met my father on Good Friday (April 7, 1944) at the Auckland Club. My father left the area in June 1944, based on my mother’s note to him:

However, Ruth and C.H. were soon reunited and joined in marriage. This is a transcript of the ARC news article:

A popular rendezvous for service men and service women for the past 20 months, the ARC Service Club in Queen Street will close at midnight on July 31, 1944. A large party will be held on Friday when the thousand volunteers will be entertained in two relays – afternoon and evening.

The director, Miss Ruth Munsell, who has many friends in Wellington, where she was director at the Cecil Club before coming to Auckland, and in Masterton, where she was previously a member of the ARC staff, was married very romantically in Auckland on American Independence Day, July 4, 1944. She met her husband, Sergeant C.H. Haug, of the United States Army, on Good Friday at the Auckland Club. She had only one day in which to prepare for her wedding and club assistants spent a hectic few hours gathering permits and licenses and perfecting arrangements. The ceremony took place at Kia Ora, which has since been closed, and which had miraculously transformed into a bower of flowers in a very short space of time.

Americans Wandering into New Zealand

At any one time between June 1942 and mid-1944, there were between 15,000 and 45,000 American servicemen in camp in New Zealand. For both visitors and hosts, this was an intriguing experience with much of the quality of a Hollywood fantasy.

The American soldier found himself ‘deep in the heart of the South Seas’ in the words of his army-issue pocket guide. He usually came to New Zealand either before or immediately after experiencing the horror of war on a Pacific island, and he found a land of milk and honey (literally), of caring mothers and ‘pretty girls.’ Little wonder that in later years, Leon Uris would write a novel about the experience (Battle Cry) and Hollywood would make a film (Until They Sail) with Paul Newman as the heart-throb.

For the host people, now in the third year of the anxieties and deprivation of wartime, the arrival of thousands of charming, well-fed young Americans with smiles on their faces and money in their pockets was like a Hollywood romance come briefly to life. New Zealanders too have recalled the experience in novels and a television drama.

The American invasion began in Auckland, New Zealand, on June 12, 1942 as five transport ships carrying ‘doughboys’ of the US Army sailed into the harbor. Two days later Marines (‘leathernecks’) landed in Wellington. They had arrived as a result of the outbreak of war in the Pacific six months before. From a New Zealand perspective, the Americans strengthened New Zealand’s defenses against possible Japanese attack. For their part, the Americans saw New Zealand as both a valuable source of supplies and a staging post for operations against the Japanese in the Pacific.

American life in New Zealand between 1942 and 1944 was centered on the camps, most of which were within marching distance or a short train journey from Wellington or Auckland. Some of the soldiers were there to train for forthcoming battles on Pacific islands. They practiced landings and jungle marches. Others had returned from the war and were there for rest and recreation or to recover their health. And there were some whose job was to provide the supplies for a modern army.

When the horror of the Pacific war got too much, the men might return to New Zealand. Some came simply for what a later generation described as ‘R & R’ (rest and recreation): a period of good food, good times and peace during which the body could recover and the mind let go of its nightmares. Others, less fortunate, returned on stretchers. Some were wounded; more came back suffering the fevers of malaria. In all, 19 hospitals were set up to take almost 10,000 patients. Cornwall Park in Auckland and Silverstream in Wellington were the sites of major institutions. To provide care and the human warmth of a familiar female accent, a considerable number of American nurses came to New Zealand. This was not just a male invasion.

Red Cross Clubs in New Zealand

Red Cross officials, nearly all of them women, organized Red Cross clubs in Warkworth, Masterton, and at the Hotel Cecil near Wellington’s railway station. There were two in the Auckland Hotel – one each for officers and enlisted men.

These clubs were oases of American culture. There was cheap American food – hamburgers, doughnuts, ice-cream sodas, Coca-Cola, apple pie, coffee. There were libraries and desks at which to write home; there were games to play, such as table tennis and pool; and there were facilities for pressing and mending clothes. The American hostesses were supported by New Zealand volunteers, who worked in the canteens and supervised the ‘wholesome’ dances that were put on at these clubs.

Whether they were New Zealanders in Cairo or Americans in Wellington, soldiers had one thing in common. Having worked hard in camp or at the front, they wanted to play hard. Young, healthy, and unrestrained by the precepts of family and community, wondering if the next month might bring death, the soldier abroad turned instinctively to pleasures of the flesh.

Drink was often the first priority. In Auckland, the Americans would make for the New Criterion Hotel in Albert St. In Wellington they would get off the train and head for the Midland in Lambton Quay or the St George in Willis St. There might be a nip of Scotch (which was rationed); then it was on to warm beer for an hour or so of the ‘swill’ before everyone was turned onto the streets at 6 p.m. Servicemen were forbidden by law from buying liquor to take off the premises, so the thirsty had to find illicit dives, purchase vinegary wine at exorbitant prices from sly-groggers, or fill lemonade bottles with ‘shell-shock,’ a concoction which was one-third port and two-thirds stout.

Then it was time to seek female company. There was a range of places where this might be found. Each American camp soon had a commercial brothel close by that did brisk business, but most men genuinely wanted companionship and good fun, and to find out a little about the country to which they had come. So they turned to more respectable meeting places. The most respectable were the dances organized at the camps themselves or at the service clubs. There was no liquor, and only ‘nice girls’ were invited. The YMCA in Auckland organized Saturday night dances at its Downtown Club. Women wore evening dresses and there were plenty of chaperones.

Those seeking a less restrained atmosphere went to a cabaret or a nightclub. In Wellington, the Majestic Cabaret became famous. There, Marines and their New Zealand partners would foxtrot or jitterbug or jive to the ‘Chattanooga Choo-choo,’ played by an excellent swing band. Auckland’s El Rey nightclub served liquor and steaks and the band played Glenn Miller hits. With women in long dresses and the Americans in their handsome uniforms, it was all very glamorous. It was hardly surprising that at such places, women agreed to more than the obligatory one dance that was expected of polite girls.

Eleanor Roosevelt Visits New Zealand

On August 28, 1943, Wellingtonians were astonished to read in their morning papers that Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady of the United States, was in town. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was a much-loved figure in New Zealand. His ‘New Deal’ had brought security and jobs to Americans in much the same way as the Savage government had given a welfare state to New Zealanders, and now ‘FDR’ was leading a new battle against Axis aggression. Eleanor Roosevelt was of course the President’s wife, but she had also established a reputation as someone with a special concern for the poor and the suffering, and a commitment to the rights of women.

On a visit to the United States, Prime Minister Peter Fraser had personally invited her and the President to New Zealand. Their son, James, a Marine, had stopped over in Auckland in May 1943. The First Lady’s arrival in Auckland was kept secret for security reasons. Once landed, she explained the aims of her mission in a broadcast to New Zealand. They were threefold: to visit the United States forces; to inspect the work of the American Red Cross, whose grey uniform she would wear throughout her seven-day stay; and finally, but by no means least, to study the contribution of New Zealand women to the war effort.

Wellington, 28-30 August 1943

With astonishing energy, Eleanor Roosevelt accomplished her purposes to the letter. Her first full round of engagements took place in Wellington (after an overnight train journey from Auckland) between Saturday 28 August and Monday 30 August. There were the expected state and civic receptions, and press conferences in which the First Lady thanked New Zealanders for their hospitality to American soldiers. Then it was off to see her fellow countrymen. She spent one morning chatting with the wounded and sick at Silverstream hospital, and another in the camps. As she had promised, she spent time at the American Red Cross Club in the Hotel Cecil. Finally, she set out to build links with New Zealand women.

I’m quite sure that Ruth Munsell met the First Lady at the ARC Club in the Cecil Hotel while Eleanor Roosevelt was on her tour of American Red Cross clubs.

On the Sunday night there was a remarkable meeting in the Majestic Theatre to which only women were invited. Eleanor Roosevelt’s arrival was announced by a waiata from the Ngāti Pōneke Young Māori Club, and she was formally welcomed by the Prime Minister’s wife, Janet Fraser. By the time she stood to speak it was obvious that the packed house, and the hundreds waiting outside to catch a glimpse of her or hear a few words, had taken her to their hearts. She described the work which women were doing in the war, showed two films, and then was treated to a thunderous rendition of ‘For She’s a Jolly Good Fellow.’ The next day she continued her investigations by visiting women employees in the Ford factory at Seaview and stopping at a hostel for women war workers in the Hutt Valley.

Rotorua, 31 August 1943

From Wellington Eleanor Roosevelt’s tour, which had begun to take on the dimensions of a royal progress, proceeded to Rotorua. There she visited Whakarewarewa in the company of the famous guide, Rangitīria Dennan (Guide Rangi). Geysers played; Māori boys dived for coins. She visited Sir Ernest Davis’s nearby farm to see the work of “land girls,” and then came a formal Māori welcome at Ōhinemutu. She discovered that ‘women do not speak there as a rule so the gods had to be invoked, but I was allowed to speak because I was a mother in a great democracy whose men were fighting with their own men,’ as she wrote in her diary, which was printed daily in the New Zealand newspapers.

Auckland, 1-3 September 1943

Another overnight trip brought the First Lady back to Auckland. This time the naval hospital was visited, as were the Red Cross and Allied Services Clubs. She even had time to drop in to the Red Cross dance in the town hall, where Artie Shaw’s band was in full swing.

Eleanor Roosevelt left New Zealand on September 3, 1943 to continue her tour to Australia and the Pacific. Leaving a charming country, she regretted that she had not been able to visit the scenic beauties of the South Island, and expressed her admiration for the work done by the women of New Zealand in factories and fields, in volunteering for Red Cross work, and in taking American boys into their homes. The photos of neatly hatted New Zealand women waving on street corners suggest that her feelings were more than reciprocated.

End of the War in the Pacific

The end of the American invasion was a more gradual process than its beginning. Many individual units would leave for battle only to return a month or two later, battered and bruised. The thinning of the American presence as a whole began towards the end of 1943.

As Japanese advances in the Pacific were turned back, secure bases closer to the action became available and the possibility of an attack on that part of the world diminished. In late October 1943, Marines began embarking on transport ships in Wellington Harbor. Three months later, the last major US force, the 43rd Division, left Auckland. Stores and offices were vacated; the Red Cross clubs ceased operation; milk bars and pubs found business slack. In October 1944, the naval base at Auckland was closed. Although some 200 Americans were still at large in New Zealand as deserters and a few naval men were to be found in the ports until VJ Day, the invasion was over.

Some New Zealanders must have felt a sense of relief. The occasional bout of fisticuffs between Kiwi and Yank during 1943 showed that for a few, the welcome had turned sour. But for many New Zealanders, the departure of the Americans was an occasion of great sadness. In many cases, the men were off to war, and there would be a time of anxious waiting as friends, lovers and acquaintances wondered whether those cheerful Americans who had wandered into their lives would survive. Perhaps they would come back sick or wounded; perhaps they would even die in New Zealand and be buried temporarily at Karori or Waikumete cemetery (after the war, the bodies were exhumed and returned to American soil).

Remembering US Memorial Day

More commonly, news would come back that they had fallen on a Pacific beach. This was especially the case with the last Marines to leave Wellington, whose assignment was to capture Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands (Kiribati). This landing turned into an American Gallipoli, with men mowed down by the Japanese as they waded ashore. More than 900 were killed and more than 2000 wounded. The columns of casualty lists printed in the Wellington newspapers made sad reading for many New Zealanders. Some were now widows. The papers began to print appeals from grieving American relatives for photos or information about their lost sons’ last days of happiness in New Zealand. On US Memorial Day in both 1944 and 1945, New Zealanders laid wreaths for the American dead.

In the long term, the memories never quite faded. New Zealand’s first full encounter with Americans and their culture gave birth to new habits – swing bands, coffee and hot dogs – which would provide fertile soil for the increasing spread of American popular culture in the next generation. Half a century on, there were many elderly women whose eyes lit up and whose feet began to tap when the subject of the invasion was raised, while their menfolk muttered about ‘those damned Yankees and our women.’

What Happened After New Zealand?

By 1948, Ruth and C.H. Haug were living in Chula Vista, CA, where Ruth’s two sisters and their young families also lived. My sister, Diane Kathleen Haug, was born in 1948, and I was born in 1950 – both of us at Mercy Hospital in San Diego, CA. My parents bought a house in Chula Vista during this time, had a horse in their backyard named Jim, and also ran a grocery store called the C&R Grocery. Our father was still drawn to the military, though, and he was in the California National Guard for several years. In 1952, C.H. reenlisted in the U.S. Army and was shipped to Japan, where we joined him. That is another story….to come later.

Kia ora, to those who served, including my parents. May you rest well. Ruth Haug died too soon in 1978 and C.H. Haug died shortly after in 1979 on Memorial Day, May 30th. I will always remember leaving William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso, Texas, after his death. The flags were at half-staff, and I thought, how did they know that my father had just died? It was Memorial Day, I realized later.

Key References:

https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/us-forces-in-new-zealand

https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/eleanor-roosevelt-visits-new-zealand

Gertrude Ruth Munsell was the granddaughter of Millard Fillmore Bowen, who was the son of Katie and Isaac Bowen, featured in my book, Lifelines – the Bowen Love Letters.

Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters is currently available on Amazon.com, at Dorrance Publishing Bookstore, and at The Last Chance Store of the Santa Fe Trail Association:

https://www.amazon.com/Lifelines-Letters-Susan-Lee-Ward/

http://bookstore.dorrancepublishing.com/lifelines-the-bowen-love-letters/

https://www.lastchancestore.org/lifelines-the-bowen-love-letters/

For comments, feel free to contact me at susanward1231@gmail.com