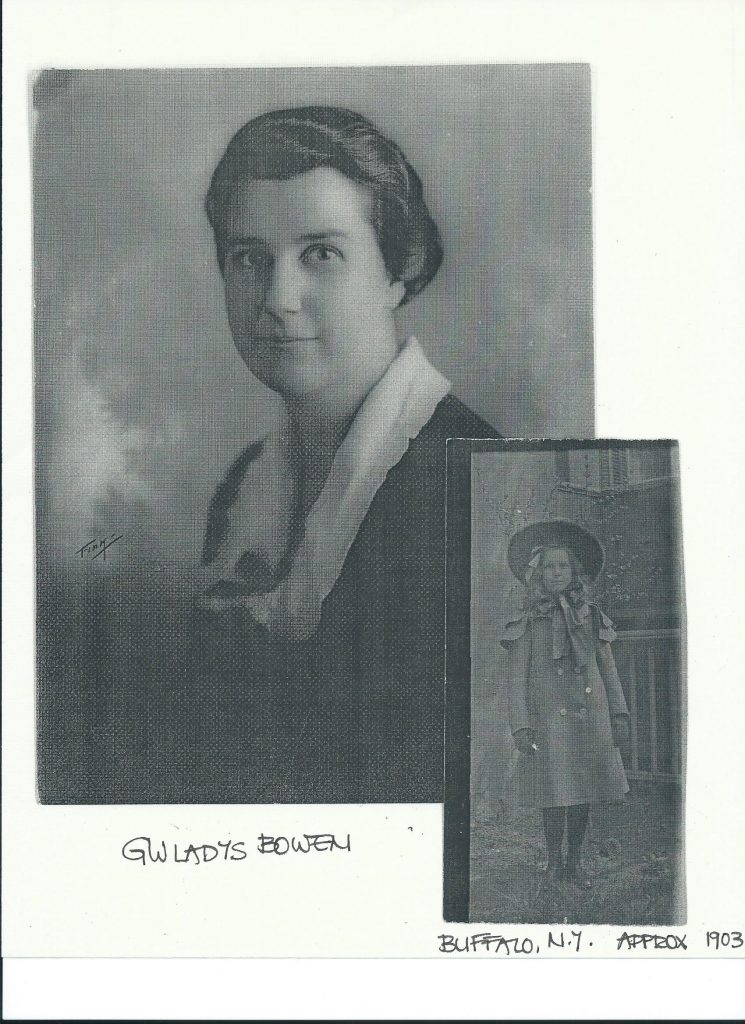

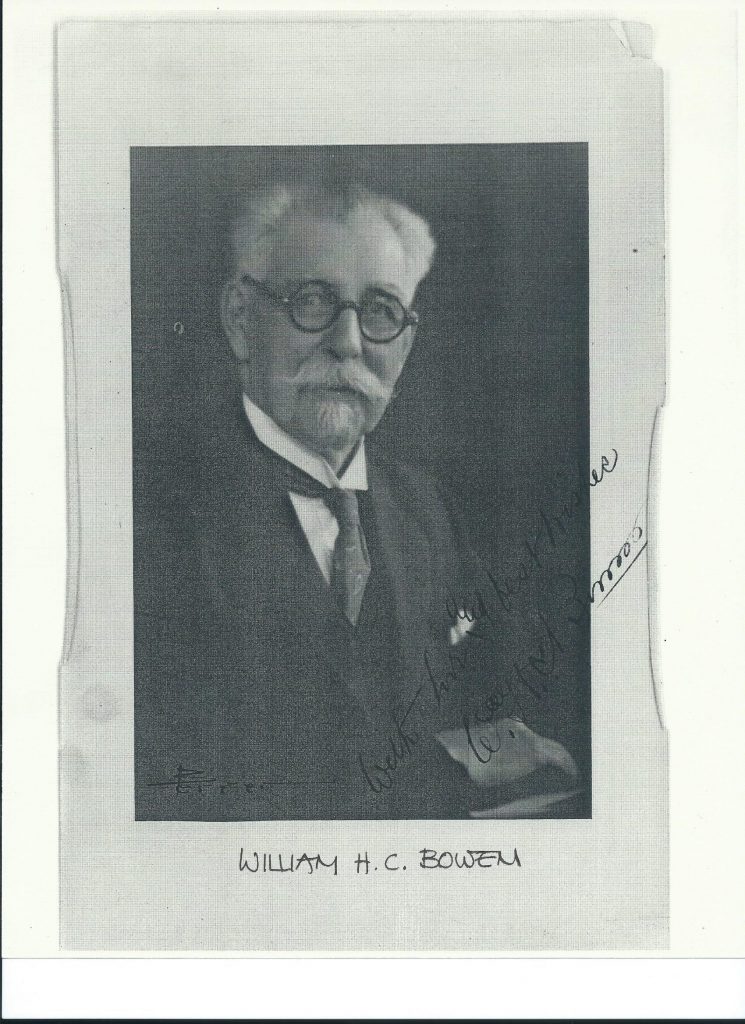

An Interview with Colonel William H.C. Bowen by Gwladys Bowen, Society Editor of The Portland Oregonian, January 7, 1930

The U.S. Army’s Camel Corps Experiment

My father, called Willie Bowen as a child, still dreams of the camels he saw at age five. He calls them his Dromedary Daydreams.

When they were posted at New Orleans in 1857, Willie’s father, Captain Isaac Bowen, and a cousin visiting from Maine, Theodore Cary, took the boy to the port at Indianola, Texas, to see the camels arrive on the USS Supply. Seeing a big ship up close was also a thrill for a small boy. The USS Supply was a ship-rigged sailing vessel that served as a “stores ship” in the United States Navy to stow and transport supplies for military purposes. She was delivering her second herd of camels, which joined the first herd from Egypt, safely unloaded at Indianola the year before. The combined herds were based at Camp Verde, Texas, known as the “camel station,” as part of the U.S. Army’s Camel Corps experiment to replace horses and mules as the primary pack animal in the southwestern parts of the country.

My grandmother, Catherine “Katie” Cary Bowen, wrote to her mother, Catherine Cary, from New Orleans on February 11, 1857:

My dear Mother, I wrote on the first and I suppose that Theodore wrote on the 2nd of the month, as he left on that day for Indianola, Texas. The camels had arrived at the mouth of the river from Egypt and a government steamer went down to take them off and carry them to Texas. Theodore could go and see the country, and from there to Florida and back here within the month, and free of cost. He wanted to go, and the Captain went to the captain of the boat and told him to pay particular attention to our nephew, so I expect he will have a nice trip if the weather is not heavy enough to make him sick.

My children are all well. Willie went with his Father and Theodore down to see the camels and was gone three days and nights. He has a slate and draws camels in every attitude. The naval officer gave them all a fine dinner and they had a splendid time, not to be soon forgotten.

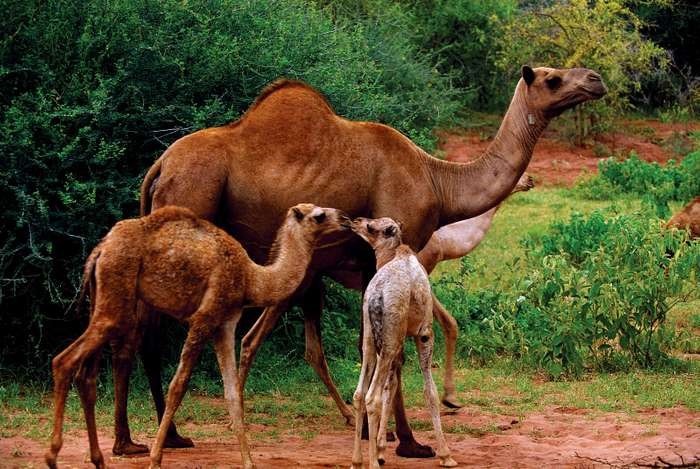

My father loves to tell the story of seventy U.S. Army camels that initially survived (a few died on the way or afterward, and calves were also born). He wishes that he had been able to ride one when on tour in Montana, just after the Battle of Little Big Horn, and later on tour at Fort Davis, Texas, in the desert southwest. He often dreams of the Bactrian camels (two humps) and Dromedary camels (one hump) that he saw off-loading on that crisp February day in 1857. As his mother mentioned, Willie Bowen drew camels on his slate for days after he returned to New Orleans.

“I didn’t know until years later that my father, Captain Isaac Bowen, actually knew and was good friends with Major George H. Crosman, who was convinced that camels would be useful as beasts of burden. My father and Major Crosman met each other during the Mexican War (1846-1848) and discussed the idea of using camels in warfare over “cracker toddy” and cigars by campfire. After the war, another Quartermaster Corps friend, Major Henry C. Wayne, conducted a detailed study and recommended to the War Department that they import camels as an experiment. Major Wayne’s ideas appealed to then-Senator Jefferson Davis, another friend from the Mexican War. Jeff Davis promoted the idea, which got traction after being appointed as Secretary of War in 1853. It made perfect sense when U.S. military forces were required to operate in arid regions like the newly-acquired desert southwest, so President Franklin Pierce (also a friend of my father’s, along with former President Millard Fillmore) and Congress began to take the idea seriously. When I was three years old, in the spring of 1855, the U.S. Congress appropriated $30,000 for the experiment.”

“Back to Major Crosman, he spent most of his military career in the Quartermaster Corps, where logistics, rather than tactics, were the most important thing. His job was to figure out how to get men and equipment most efficiently from one place to another. My father, Captain Bowen, was an Artillery Officer, but he became reacquainted with Crosman after the Mexican War. Both were stationed in or around Philadelphia, and I know from my mother’s letters that she kept up with the Crosman family for years. At one point while stationed at Fort Mifflin in 1849, my parents hosted several Crosman boys for two weeks, and both families lived at Schuylkill Arsenal the following year. Even from our posting at Fort Union, New Mexico Territory, my mother wrote to hers in 1852 about Crosman family news.”

Major George H. Crosman was among the first officers in the U.S. Army to advocate the military use of camels for transportation of supplies. Ten years before the start of the Mexican War, Crosman submitted an extensive study on the subject of camels (also called “ships of the desert”) to his superiors, proposing a U.S. Army Camel Corps. He and Isaac Bowen discussed this over a campfire with “cracker toddy” and cigars during the Mexican War.

The Experiment Was Underway

“The great camel experiment was underway after the second herd arrived at Indianola that day in 1857. I was enthralled with camels and drew them constantly. I had no idea that despite their strong association with the Middle East and Africa, camels originated in North America about 45 million years ago. They also ambled down to South America, where they evolved into llamas and alpacas. My father had to eventually drag me away from watching them, and when he could find picture books of camels, he bought them for me. What I saw that day on the dock was their unmistakable silhouette with their humped backs, short tails, long slim legs, and long necks that dipped downward, and then rose to a small narrow head. Their upper lips are split into two sections that move independently, and they are about ten feet long and over six feet high at the hump. I was told by camel breeder and trainer Hadji Ali (Hi Jolly, a.k.a. Philip Tedro) that male camels weigh about 900 to 1,400 pounds and females are about 10 percent smaller. They are usually light brown, have heavy eyelashes to protect their eyes from blowing sand, and their nostrils can be squeezed shut. He demonstrated and explained that camels are generally docile, but they can bite or kick when annoyed, like having their nostrils pinched! Coming off the ship, I saw camels huff so sharply that they spit out undigested food. My father had to keep me from trying to pet their legs, like I was used to with a horse or mule.”

What Happened to the U.S. Army’s Camels?

After arriving at Camp Verde, over the next several months small caravans traveled from San Antonio to El Paso, and throughout the region, and finally ended up in Yavapai County, Arizona. The experiment was generally deemed successful. The camels were praised for their speed, endurance, strength, and adaptability. The praise mostly came from the persons promoting the camel corps experience, but the Regular Army soldiers were not as agreeable to the strange creatures and they reported the following liabilities: the camels had a strong, distinct odor, they were forever spitting, and the Army’s burros, horses and mules were afraid of them. Each camel was outfitted with a camel bell, which also spooked animals around them. They also had razor-sharp teeth and occasional aggressiveness. All of these were a bad mix that made them unpopular with the soldiers who worked with them.

Doomed, But Not Failed

The camels were stationed in Camp Verde, in central Texas, along the road from San Antonio to El Paso, and beyond to California. In June 1857, under orders from Washington, the herd was split and more than two dozen were sent on an expedition to California, led by Edward Fitzgerald Beale. Five months later, Beale’s party arrived at Fort Tejon, an Army outpost a few miles north of Los Angeles. A California paper written by A.A. Gray in 1930 noted the significance of that journey: “[Beale] had driven his camels more than 1,200 miles, in the heat of the summer, through a barren country where feed and water were scarce, and over high mountains where roads had to be made in the most dangerous places…He had accomplished what most of his closest associates said could not be done.”

Back east, the Army put the remaining herd to work at Camp Verde and at several outposts in the Texas region. Small pack trains were deployed to El Paso and Fort Bowie. In 1860, two expeditions were dispatched to search for undiscovered routes along the Mexican border. By that time, though, Congress had also ignored three proposals to buy additional camels – the political cost seemed to be too high. The mule lobby did not want to see the importation of more camels, for obvious reasons, and they lobbied hard in Washington against the camel experiment.

If the mule lobby didn’t end the experiment, the Civil War did. At the dawn of the war, after Texas seceded from the Union, Confederate forces seized Camp Verde and its camels. “They were turned loose to graze and some wandered away,” Popular Science reported in 1909. “Three of them were caught in Arkansas by Union forces, and in 1863 they were sold in Iowa at auction. Others found their way into Mexico. A few were used by the Confederate Post Office Department.” One camel was reportedly pushed off a cliff by Confederate soldiers. Another, nicknamed Old Douglas, became the property of the 43rd Mississippi Infantry, was reportedly shot and killed during the siege of Vicksburg, then buried nearby.

By late 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, the camel experiment was essentially finished. The California camels, moved from Fort Tejon to Los Angeles, had foundered without work for more than a year. In September, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered the animals be put up for auction. An entrepreneur of the frontier named Samuel McLaughlin bought the entire herd in February 1864, then shipped several camels out to Nevada to haul salt and mining supplies in Virginia City. McLaughlin raised money for the trip by organizing a camel race in Sacramento and a crowd of 1,000 people reportedly turned up to watch the spectacle. The animals that remained in California were sold to zoos, circuses, and even back to Beale himself. As was reported, “For years one might have seen Beale working camels about his ranch and making pleasure trips with them, accompanied by his family.”

The Texas herd was auctioned off shortly thereafter, in 1866, to a lawyer named Ethel Coopwood. For three years, Coopwood used the camels to ship supplies between Laredo, Texas, and Mexico City — and that’s when the trail starts to go cold.

Remembering the Camels

My father remembers 1857 well, despite being only five years old. He remembers that year more than what he had for breakfast this morning! It was the same summer when he, his mother, and younger siblings traveled back to Houlton, Maine, to spend the summer with his mother’s family, and then on to Buffalo, New York, to spend time with his father’s family. All of the children caught the measles in Buffalo, which delayed their return to their father, Isaac Bowen, in New Orleans. Willie Bowen had proudly gone to school in Houlton with his cousin, Willie Cary, and got into a fight with a kid who didn’t believe his camel story. Willie Bowen drew the kid a picture on his slate for illustration, but ended up with a bloody nose.

Father eventually got to ride on a tired and bored camel at a circus in California, which was not nearly as memorable as staring up the nostrils of a camel at age five!

Resources:

https://www.nps.gov/whsa/learn/upload/Ancient_Camel_09_23_16_-258KB_PDF.pdf

https://www.history.com/news/giant-ancient-camel-roamed-the-arctic

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Camel_Corps

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/whatever-happened-wild-camels-american-west-180956176/

https://www.britannica.com/animal/camel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Camel_Corps

My book, Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters, is currently available on Amazon.com, Dorrance Publishing Bookstore, and The Last Chance Store of the Santa Fe Trail Association:

https://www.amazon.com/Lifelines-Letters-Susan-Lee-Ward/

http://bookstore.dorrancepublishing.com/lifelines-the-bowen-love-letters/

https://www.lastchancestore.org/lifelines-the-bowen-love-letters/