Saving the U. S. Postal Service should be on everyone’s mind. The predecessor of the U. S. Postal Service, the Post Office Department, was created in 1775 as America’s first communication network. It not only facilitated commerce, but it also strengthened the bonds between families and friends, and united a new nation. And of course, politics played a role, and that hasn’t changed.

Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.

While the Postal Service has no official motto, the popular belief that it does is a tribute to America’s postal workers. The words above, thought to be the motto, are chiseled in gray granite over the entrance to the New York City Post Office on 8th Avenue and come from Book 8, Paragraph 98, of The Persian Wars by Herodotus. During the wars between the Greeks and Persians (500-449 B.C.), the Persians operated a system of mounted postal couriers who served with great fidelity.

Public Service As Highest Aim

The U.S. Postal Service has now served our country for 245 years by adapting to the changing needs of our nation and fulfilling its historic mission stated in Title 39 of the U.S. Code:

The Postal Service shall have as its basic function the obligation to provide postal services to bind the Nation together through the personal, educational, literary, and business correspondence of the people. It shall provide prompt, reliable, and efficient services to patrons in all areas and shall render postal services to all communities.

As our country grew, people in new states and territories petitioned Congress for even more post routes, regardless of their cost or profitability. The Post Office Department, and thus the federal government, had to decide whether to subsidize routes that promoted settlement, but did not generate enough revenue to pay for themselves or to operate in the black. The Department struggled with this issue. With congressional support and keeping fiscal responsibility firmly in mind, the Department ultimately made decisions in the 19th century that reflected public service as its highest aim. It funded post routes that supported national development and instituted services to benefit all residents of the country.

19th Century Modes of Carrying Mail

At the turn of the 19th century, when the nation’s waterways were its main transportation arteries, travel often depended on river currents, wind, and muscle. Traveling upstream on some rivers was so difficult that boat owners sometimes sold their vessels upon reaching their destination and returned home overland. Robert Fulton launched America’s first successful steamboat line, connecting New York City and Albany via the Hudson River, in September 1807. Although Fulton’s steamboats traveled at only six miles per hour, their dependability revolutionized travel. As long as their fires were fed, the boats’ boilers created steam, turning the paddlewheels.

By the late 1820s, the Post Office Department contracted for mail to be carried by steamboats along the East Coast, although mail contractors continued to use stagecoaches on parts of the routes, and then exclusively when waterways were clogged by ice in the winter. In the 1830s, the Post Office Department greatly expanded its use of steamboats. Contracted service began on the Ohio River, but no further west. Then in 1837, service west of Louisville to New Orleans began, although many merchants continued to send their correspondence outside of the U.S. Mail, postage-free. Unfortunately, the average lifespan of an antebellum steamboat on the Mississippi River was five to six years. Daily hazards included explosions, fires, collisions, and snags. In 1851, as detailed in Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters, steamboats were often damaged and significantly delayed by snags when Katie and Isaac Bowen traveled from Buffalo, New York, to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Due to the level of the rivers at that time, the Bowens did not experience inconveniences on that trip, other than having to filter muddy river water for drinking.

Currier & Ives produced more than 200 lithographs depicting the steamboats that navigated our nation’s great rivers, such as the Hudson and the Mississippi. The boats were celebrated as examples of industrialization and the firm often documented the latest advances in technology. Here, The Mayflower is shown cruising gently as it traveled between St. Louis and New Orleans. It was destroyed by fire in 1855 after less than a year of service.

My particular in interest in the U.S. Postal Service is related to my research for Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters, and how mail was sent and received between Maine and Mexico in the 1840s by steamboats to major seaports and military forts on the Gulf of Mexico, and later across the country by a combination of steamboats, horseback, wagon trains, stagecoaches, and by military and contracted mail carriers who rode day and night across the Santa Fe Trail in the 1850s.

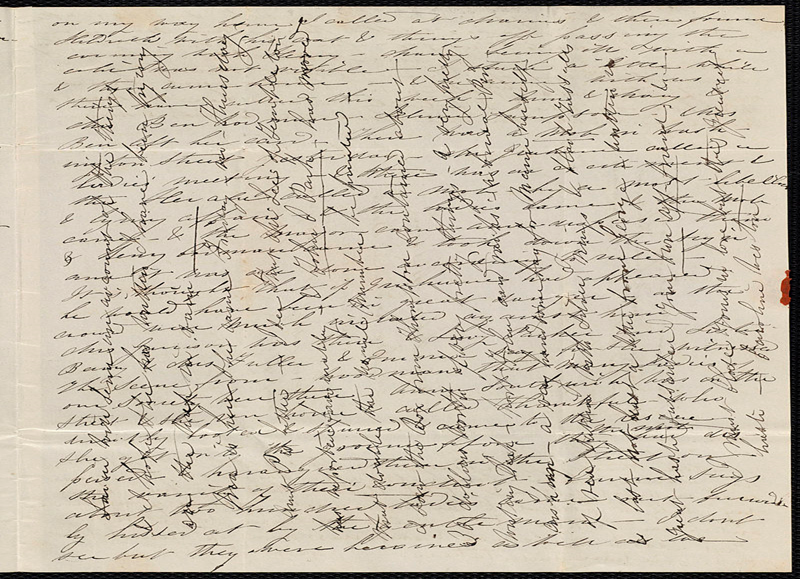

As with the correspondence between Katie and Isaac Bowen, their friends and family members, the cost of postage constantly changed and many people continued to rely on friends and merchants to carry their mail, thus avoiding fees. By the middle of the 19th century, the Post Office Department simplified and lowered postage rates. Before that, postage was based on the number of sheets in a letter and the distance a letter traveled. Families, friends, or businesses further distant paid more to keep in touch. People rarely used envelopes, which would have counted as another sheet, so they simply folded their letter so that the outside was blank and sealed it with wax or an adhesive wafer. To fit even more lines on one page, some people cross-wrote their letters. When they reached the end of the page, they turned the paper 90 degrees and continued writing.

Over the course of twelve years, Katie Bowen wrote a few letters using this cross-writing technique. It was also called cross-hatching. The letters are almost impossible to read! She also had to use notepaper on occasion when letter paper was scarce.

My dear Husband,

Do you wonder at this freak of writing upon notepaper? Well, there’s not a sheet of paper to be had in town and necessity is the mother of invention. Somebody will think it a nice love letter, and so it is, to the best husband that ever lived, from his own dear Katie.

During the Mexican War 1846-1848, newlyweds Katie and Isaac Bowen were separated for three years, but wrote to each other every Sabbath and numbered their letters to make sure they were all received. Amazingly, most of them were, except for letters that were captured by the Mexican Army and letters that occasionally sank with ships traveling from Camp Point Isabel (later called Fort Brown) in Texas to New York and Boston. Katie Bowen often wondered that their letters were received at all, given the distance they had to pass over, and with so many eyes to rest upon them. She called the mail service “the mails.” She and Isaac both depended on “the mails” for news of health and well-being, and especially for reassurance.

On May 21, 1846, Katie Bowen wrote to Isaac Bowen from Houlton, Maine. Isaac was at Camp Point Isabel, Mouth of the Rio Grande, at that time, prior to his regiment joining the rest of the U.S. Army in Northern Mexico:

My dear Husband,

On Tuesday I received your kind letter directed to me at Boston and truly it was a solace to a poor lonely soul to once more behold your handwriting, though the letter did not contain one half I wished to know respecting your comfort and feelings about going to so dreadful a place. We have received expresses from Boston with news from Mexico up to the 15th. I pray that a merciful power may watch over and shield thee from danger. I watch for the mails like one whose only hope depended upon the intelligence there found.

On April 9, 1848, Katie Bowen wrote to her husband, who was in Saltillo, Mexico:

I am still without intelligence from my own dear Isaac. What can it mean? Eight mails have passed and as many times have I been disappointed. All I know is that the time seems very long and the weeks are insupportable without thy tribute of affection.

By the end of 1850, Isaac Bowen was promoted to Captain, Chief of Commissary for the newly established New Mexico Territory. He and his wife traveled by a series of steamboats from Buffalo, New York, to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where civilian and military wagon trains prepared to head west.

On April 15, 1851, Katie wrote to her parents from Fort Leavenworth about their journey from Buffalo:

Our goods are in a good state of preservation and the worst of our journey is over. We were four days and a half coming from St. Louis and we met with no trouble. It is a dreadful river to navigate, and we overtook a steamboat hung up on a sandbar that started a day before us, and another that started a week before we passed the same way down the river. It was full of passengers, but had broken a shaft in attempting to get off a sandbar, and there the people were laying until the boat can be repaired. Our captain did not see fit to take them off. I never saw such a river, perfectly thick with mud, full of snags and sandbars, and the pilots had to go entirely by the lead to ascertain the depth of water. I am thankful that we are off these rivers.

Regarding mail service, Katie Bowen wrote to her parents on May 17, 1851, from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas:

My dear Father and Mother,

It is not entirely settled yet where headquarters will be, but at any rate we will be wherever it is, and at present you had better direct all letters to Santa Fe, New Mexico, via Independence, as all mails are made up there once a month. But you must write as often as once in ten days so as to be sure of some hitting the monthly mail package. If you wrote once a month, it would be a day too late, and have to lay over till next time. Even if I knew the day, which I do not, that the mails start, you would have to allow three weeks for it to reach Independence, so please write often until we can discover how regular the carriers start.

The Bowens kept up correspondence with family and friends while posted at Fort Union, Albuquerque, and Santa Fe between 1851-1855. Mail from Katie’s home in Maine was received approximately once a month and was highly anticipated. Katie frequently asked her parents to mail small, light-weight items that she couldn’t buy in New Mexico, like handkerchiefs, shoelaces, caps, thread, and lace.

September 1, 1852 Fort Union, New Mexico Territory

My dear Father and Mother,

As I have said before, we get nothing but silver here and it cannot be sent in letters, but I guess you will trust me. I will pay postage on this end of the line. The little cap you sent me is very pretty, even more so than the one I had, which has been greatly admired, and the maker could realize a fortune here at short notice.

October 1, 1854 Albuquerque, New Mexico

My dear Mother,

I do not know what I should do if the mails were not regular. Your letters keep me in thinking matter for a whole month and I am never weary of reading them.

Westward Ho

Following the discovery of gold in California, immigration exploded. As the population grew, so did the need to connect the new territories with the rest of the country through the U.S. Mail. Over the years, several overland mail routes were established, but service was erratic based on extreme weather conditions, Indian attacks, the lack of water, and the scarcity of mules. Passengers who rode in mail wagons sometimes had to get out and walk, or even help push the mail wagons.

The Butterfield Overland Mail Company operated from 1858 to 1861 under contract with the U.S. Postal Department, providing transportation of U.S. mail between St. Louis and San Francisco. The route proposed by Butterfield became known as the Oxbow Route because of its shape on the map – starting in St. Louis and dipping southwesterly through Missouri, western Arkansas and the Indian Territory, turning west across Texas and southern New Mexico and Arizona, and then curving north again in California, finishing in San Francisco. Scheduled semiweekly service on the Butterfield Overland route began on September 15, 1858 and the specified running time was 24 days, but within a year, the average trip time had been shaved to about 21 ½ days. Even the loudest critics of the route’s location had no complaints about the service.

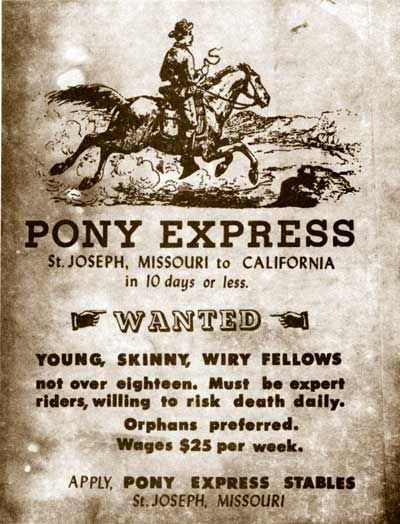

The Pony Express service (formally named the Central Overland California & Pike’s Peak Express Company) started in 1860, after Katie and Isaac Bowen’s story ends, but express riders who traveled the Santa Fe Trail during their time were well known – particularly the exploits of Francis X. Aubry, sometimes called the Telegraph of the Plains. On October 26, 1861 – two days after the transcontinental telegraph line was completed – the Pony Express officially ended. It became one of the enduring legends of the West.

The Postal Service Strengthens Our Democracy

I couldn’t have said it better. Excerpted from Postmaster General and CEO, Megan J. Brennan, in 2015:

At the beginning of our nation, and in the midst of the war for independence, there was a critical need to bind the people together through a reliable and secure system for the exchange of information and the delivery of correspondence. This led to the creation of America’s postal system in 1775, which preceded the birth of our country. The U.S. Postal Service has played a vital, sustaining, and unifying role in the life of the nation and in the lives of the American public ever since.

The history of the Postal Service is a large story set on a broad canvas. It is intertwined with the history of America, and it provides a lens from which we can observe the evolution of our nation. The postal system strengthened the foundations of our democracy by fostering the flow of ideas and access to America’s free press. It enabled the vast expansion of American industry and commerce, spanning and influencing the rise of the railroads in the 19th century, air travel in the 20th century, and the advanced digital technology of recent decades.

The Postal Service continues to play an indispensable role in every American community. From connecting people to each other, to businesses, and to their government, one doorstep and one mailbox at a time, the Postal Service continues to bind the nation together.

Resources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herodotus

https://about.usps.com/publications/pub100.pdf

https://about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-history/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Xavier_Aubry

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Butterfield_Overland_Mail

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Xavier_Aubry

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pony_Express

My book, Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters, is currently available on Amazon.com, Dorrance Publishing Bookstore, and The Last Chance Store of the Santa Fe Trail Association:

https://www.amazon.com/Lifelines-Letters-Susan-Lee-Ward/

http://bookstore.dorrancepublishing.com/lifelines-the-bowen-love-letters/

https://www.lastchancestore.org/lifelines-the-bowen-love-letters/