Biodiversity refers to the amount of diversity between every living thing, including plants, bacteria, animals, and humans in a given habitat at a particular time. Biodiversity boosts ecosystem productivity where each species, no matter how small, all have an important role to play. For example, a larger number of plant species means a greater variety of crops. Greater species diversity ensures natural sustainability for all life forms. And we all know what “to boogie” means in this context – to dance and celebrate our biodiversity.

The different varieties and types of animals and plants that live on the Great Plans is an example of biodiversity, and relates to observations made in Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters.

Published in 1844 and 1845

The Great Plains is a broad expanse of flat land, much of it covered in prairie and grassland, located in the interior of North America. It lies west of the Mississippi River tallgrass prairie in the U.S. and east of the Rocky Mountains in the U.S. and Canada. In Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters, Captain Isaac Bowen and his wife, Catherine “Katie” Cary Bowen, traveled across the Great Plains on the Santa Fe Trail in 1851 during their journey from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to the newly created supply depot for the New Mexico Territory, Fort Union.

On their three-month journey along the Santa Fe Trail by wagon train, Katie Bowen promised to send a prairie rattlesnake to her brother, Shepard Cary, back home in Houlton, Maine. This was highly impractical, of course! On June 25, 1851, after five days on the trail, Katie wrote to her mother:

Tell Shepard that I cannot send him a rattlesnake now because we have not seen any, but I enclose a piece of snakeskin that I just picked up beside our tent. We are not disturbed at night by anything when the mules hold their tongues. They cry for corn sometimes, and do not get so well satisfied with this grass as with hay and corn.

The Bowens were just at the start of their trip when Katie wrote to her mother three weeks later, from an unknown location on the Santa Fe Trail:

Wolves are barking all about us and a few moments ago, Mr. Martin called to us to bring him a stick to kill a rattlesnake and sure enough, he killed one seven years old. It’s back was broken and the venomous thing bit itself in a dozen places and covered the end of a stick with poison. We had him securely buried and burned the weapon that killed him. Isaac got the rattles, which I send to Matty.

A week later, writing to her mother from Cow Creek on the Santa Fe Trail, Katie mentioned prairie dogs, rattlesnakes and owls:

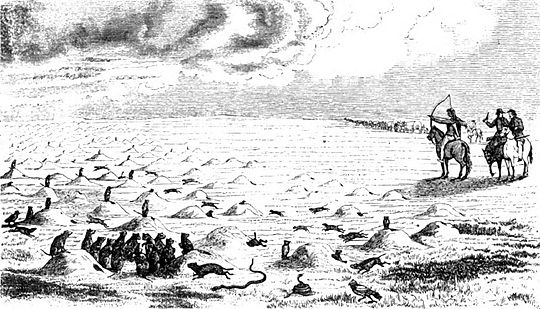

For several days we have been passing through “dog towns.” They cover acres and acres, little holes a few feet apart and deeper than anyone knows. They are as big as kittens a week or two old, and when we approach, sit at the opening of their holes and bark right sharply, wag their little tails and disappear. We frequently see owls sitting on their holes and are told that with the rattlesnake, they make a charming society in their houses.

Here we are fairly among the Raton Mountains at a small stream without a name, but a tributary to the Purgatory. Pretty name, isn’t it? I have not noted much since writing last, but some little things of importance have occurred. Among the prominent ones, Isaac shot a rattlesnake today eleven years old, so the rattles indicated.

Katie Bowen was well-educated, but having been born and raised in Houlton, Maine, she wasn’t familiar with the diversity of grasses, plants, animals, insects, and weather found on the Great Plains. Nor the diversity of the Indian tribes they encountered while traveling from Kansas to the New Mexico Territory. She frequently mailed seeds, grasses, and pressed flowers to her father, William Holman Cary, Sr., back home in Houlton.

On the trail, Katie was told by a seasoned traveler about the mutually beneficial relationship existing between prairie dogs, rattlesnakes, and owls. Black-tailed prairie dogs, prairie rattlesnakes, and burrowing owls, to be exact. But was the relationship mutually beneficial, or just opportunistic?

Black-Tailed Prairie Dogs

Prairie dogs are an important component of the ecosystems they inhabit. They directly and indirectly influence grasslands through their grazing and burrowing, and as prey. Through their foraging and clipping of vegetation to maintain their habitat, as well as the mixing of subsoil and topsoil during excavations, prairie dogs affect the redistribution of minerals and nutrients, encourage penetration and retention of moisture, and affect plant species composition. Although they reduce the biomass of vegetation, they often also enhance the digestibility, protein content, and productivity of grasses that are preferred by large herbivores.

Prairie dog burrows and colony sites provide shelter and nesting habitat for a variety of animals, including insect and arachnid species, burrowing owls (Athene cunicularia), mountain plovers (Charadrius montanus), horned larks (Eremophila alpestris), and black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes). Among the animals that consume prairie dogs are black-footed ferrets, American badgers (Taxidea taxus), long-tailed weasels (Mustela frenata), bobcats (Felis rufus), coyotes (Canis latrans), ferruginous hawks (Buteo regalis), golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetoes), prairie falcons (Falco mexicanus), bull snakes (Pituophis melanoleucus), and prairie rattlesnakes (Crotalus viridis). Additional mammals occasionally prey on prairie dogs; e.g., various fox species.

Within colonies, prairie dogs live in family groups called coteries. The size of a coterie ranges from 1 to 26, but a coterie generally consists of 1 breeding male, 2-3 adult females, and 1-2 yearling offspring of each gender. A coterie maintains a well-defined territory that is defended from prairie dogs of other coteries. Most females live their entire lives within their natal territory, while most males remain in the natal territory for only one year. After their first year, males disperse to another territory within the colony site, or to another colony.

The Howdy Owl and the Prairie Dog

Nature is filled with examples of one species benefiting from the efforts of another. Take the Burrowing Owl and the tunneling species that unwittingly build their nests. The charismatic, pint-sized owls have stilt-like legs that help them spot predators, but aren’t ideal for digging, so they rely on animals custom-built for the task, including prairie dogs, to do it for them.

Keystone species are those animals that tend to hold an ecosystem together, and whose presence or absence has the greatest effect on the well-being of the other species. Perhaps no other North American animal can claim so many uninvited guests as the prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus), and perhaps the most charismatic of these is the Burrowing Owl. The seemingly curious, if not actually friendly, manner of the Burrowing Owl when approached by humans is probably the reason that in some parts of the American West, cowboys called them “Howdy” Owls.

The usual rules of owl decorum do not apply to Burrowing Owls. First, they are not as highly nocturnal as most other owls, but instead are active mainly during broad daylight. Their retinas lack the reflective surface that increases nocturnal visual sensitivity and produces the “eye shine” typical of most owls. Secondly, unlike the larger owls of the grasslands, Burrowing Owls are surprisingly insectivorous, at least during the summer months when large, slow-moving insects, such as dung beetles (Scarabaeidae spp.) and ground beetles (Carabidae spp.), are abundant around dog towns and are easily captured. Thirdly, Burrowing Owls seem to lack the acute binaural hearing and precise sound source localization (where the sound originates) abilities that owls as a group are primarily noted for, and instead appear to rely on their keen daytime vision for prey-finding. In correlation, their faces have only poorly developed facial disk feathers surrounding their ears, which help funnel extremely faint sounds into the ear canals of the most highly nocturnal owls.

When a Burrowing Owl is confronted by an approaching human, it is more likely to stay put than to fly away immediately. Often, after a few slight horizontal or vertical head movements by the bird, which are probably designed to get a better distance estimating fix on the new intruder into its personal space, the owl will probably duck back into its hole. Or, if perched on a post, it may take silent flight over the prairie dog town and land near its burrow entrance. When cornered in its burrow, a Burrowing Owl will produce a sound that mimics a rattlesnake’s rattle, and may also spread and tilt its wings vertically, apparently to make itself appear larger and more dangerous. The male’s courtship call is usually soft and owl-like, but adults of both sexes also utter a rapid chatter when alarmed or while defending the nest.

Although a Burrowing Owl is perfectly content to take over a prairie dog burrow without making major structural changes or other renovations, it’s likely to gather fragments of dried bison or cattle dung, break them into small pieces, and line the entrance area in front of its burrow with these bits of debris. Such markings help one to recognize an active Burrowing Owl burrow, as do the dried owl pellets that are usually rich in chitinous insect fragments, such as the undigested exoskeletal remnants of grasshoppers and scarab and carabid beetles. It has been suggested that the presence of dung may help attract dung beetles to the nest, where they can be easily captured by the owls.

On the Great Plains, it is primarily the black-tailed prairie dog that offers the owls housing. Besides being able to exploit inactive dog burrows, the owls favor the combination of low shrub coverage, short vegetation, and high percentage of bare ground that is typically present in prairie dog colonies. When the ground-level vision is variously obstructed, the birds find suitable nearby observation posts to use, such as fenceposts or boulders. Within prairie dog towns, Burrowing Owls favor larger and active colonies. Typically, a town that has been abandoned by prairie dogs will also be abandoned by Burrowing Owls within three years, perhaps largely as a result of encroachment of dense vegetation, but also because of the gradual deterioration of the burrows themselves.

Within active towns, the owls often choose nests near the periphery of the colony, where there may be a greater abundance of insects, more available nearby perches, and a proximity to foraging areas. Burrowing Owls may also favor sites offering several “satellite” burrows, used by both adults and young, perhaps to avoid the buildup of nest parasites and loss of an entire family to predators. As many as five such satellite burrows may be used by a single owl family, which may contain a half dozen or more owlets of varying ages and sizes

There is no proof that prairie dogs directly benefit from the presence of Burrowing Owls, and the ever-alert rodents sometimes utter alarm notes when the owls fly overhead, suggesting that prairie dogs are at least somewhat wary of the owls.

Prairie Rattlesnakes

Amusing stories have been told of the amicable relationship existing between prairie dogs (barkers), rattlesnakes (rattlers), and Burrowing Owls (hooters), but they appear to be untrue. In fact, prairie rattlesnakes will eat owl and prairie dog young, which is not a very neighborly gesture. However, these venomous snakes will live in prairie dog tunnels once the original inhabitants have left or been digested.

As its name implies, the prairie rattlesnake’s range is centered in the middle of the United States, from Canada south to Texas and from Idaho east to Iowa. Growing around 35-45 inches in length, the snake is usually a greenish gray, olive green or greenish brown, though some are light brown or yellow. Unsurprisingly, the rattlesnake has a rattle, to which it adds a new segment each time it sheds its skin.

Crotalus viridis (common names are prairie rattlesnake, western rattlesnake, Great Plains rattlesnake) is a venomous pit viper species native to the western United States, southwestern Canada, and northern Mexico.

Generally, western rattlesnakes occupy areas with an abundant prey base. Many subspecies occupy somewhat rocky areas with outcrops serving as den sites. Western rattlesnakes have also been known to occupy burrows of other animals, like prairie dogs. They seem to prefer dry areas with moderate vegetation coverage. Vegetation cover will vary depending on region and subspecies.

Western rattlesnakes live on the land, but they can sometimes climb trees or bushes. They are typically active diurnally in cooler weather and nocturnally during hot weather.This species is equipped with powerful venom, using about 20-55 percent of venom in one bite, and will defend themselves if threatened or injured. As with other rattlesnake species, western rattlesnakes will rapidly vibrate their tails, which produces a unique rasping sound to warn intruders. The venom of the western rattlesnake is a complexly structured mixture of different proteins with enzymes such as proteases and peptidases found among them. Besides the hemotoxine and its tissue destructive effect, the venom also has neurotoxic properties.

Western rattlesnakes, because of their expansive distribution, have a wide array of prey. Generally, this species prefers small mammals such as ground squirrels, ground nesting birds, mice, rats, small rabbits, and of course, prairie dogs.

The Sounds They Make

Barkers

Rattlers

Hooters

Doing research for Lifelines – the Bowen Love Letters, I was interested in the archetypal cohabitation story of the prairie dog, rattlesnake, and owl. It appears to be a biodiversity myth. But now I have my own owl story.

We are fortunate to live near a protected greenbelt just north of a major urban area, with a spring-fed creek that runs for twenty-seven miles. In the past two years, we’ve seen occasional coyotes, foxes, possums, and racoons, but mostly squirrels, lizards, tree rats, garter snakes, and a wide variety of birds (including raptors). This summer, we had the privilege of meeting Olivia and the twins, as we have named a friendly neighborhood family of Barred Owls who show up at dusk. We also see them in the mornings sometimes, and when not dive-bombing our dog in the back yard, they tend to sit on tree branches or a neighbor’s roof, hooting at each other, swiveling their heads while listening for prey.

When Olivia (the mom) hoots, she puffs up her cheeks and makes this amazing sound: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ls-vgejzq_8

When very small, the owlets swayed on our hammock and pecked at the ground. Now several weeks older, one of them hoots properly, but the other owlet still makes a loud gurgling noise when diving for prey. It’s like a teenage boy whose voice is changing.

The owls seem to coexist with our dog now and we’re not concerned about them trying to grasp Vanna White in their talons. She weighs 60 pounds, so she’s too heavy for them to pick up anyway. Now that they know each other better, Vanna White just stands out in the backyard wagging her tail, looking up, which lets us know that the owls are nearby.

Fun Facts about Barred Owls:

- The Great Horned Owl is the most serious predatory threat to the Barred Owl. Although the two species often live in the same areas, a Barred Owl will move to another part of its territory when a Great Horned Owl is nearby.

- Pleistocene fossils of Barred Owls, at least 11,000 years old, have been dug up in Florida, Tennessee, and Ontario.

- Barred Owls don’t migrate, and they don’t even move around very much. Of 158 birds that were banded and then found later, none had moved farther than 6 miles away.

- Despite their generally sedentary nature, Barred Owls have recently expanded their range into the Pacific Northwest. There, they are displacing and hybridizing with Spotted Owls—their slightly smaller, less aggressive cousins—which are already threatened from habitat loss.

- Young Barred Owls can climb trees by grasping the bark with their bill and talons, flapping their wings, and walking their way up the trunk.

- The oldest recorded Barred Owl was at least 24 years, 1 month old. It was banded in Minnesota in 1986, and found dead, entangled in fishing gear, in the same state in 2010.

Resources Used for This Essay

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crotalus_viridis

https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/burrowing-owl