Like many of us, I had ancestors who traveled on the Santa Fe Trail. In my case, it was my great-great-grandparents, Captain Isaac Bowen and his wife, Catherine “Katie” Cary Bowen. Their first trip on the Trail in 1851 was by military wagon train from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to Fort Union, New Mexico Territory. That arduous and dangerous journey took three months for various reasons, as detailed in Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters (Part Three: The Santa Fe Trail). Their second trip across the Santa Fe Trail, five years later, was back to the states from Fort Union and that trip took just a few weeks by a series of stagecoaches.

The Santa Fe National Historic Trail

The Santa Fe National Historic Trail is one of 19 official national historic trails in the United States. While these trails are separate and have their own routes and existed in different historic periods, they all are significant to our country’s history. National Historic Trails are designated to protect the remains of significant overland or water routes that reflect the history of our nation. They represent the earliest travels across the continent on the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail; our nation’s struggle for independence on the Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail; epic migrations on the Mormon and Oregon Trails, and the development of continental commerce on the Santa Fe Trail. They also commemorate the forced displacement and hardships of the Native Americans on the Trail of Tears.

The Santa Fe Trail – America’s First International Commercial Highway

In 1821, the Santa Fe Trail became America’s first great international commercial highway, bringing people, goods, and ideas to and from the Mexican provincial capital of Santa Fe. For nearly sixty years thereafter, it was one of the nation’s most-commonly traveled routes of western expansion. Mindful of this, the Santa Fe Trail Association (SFTA), a non-profit association with a 501 (c)(3) status, was created in 1986 to help protect and preserve it. The U.S. Congress likewise recognized the significance of the Santa Fe Trail to American history by proclaiming it a National Historic Trail in 1987.

Brief History of The Santa Fe Trail 1821 – 1880

Long before the creation of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, and before the Interstate Highway System was funded by the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, one enterprising entrepreneur, William Becknell, published a notice in the Missouri Intelligencer newspaper on June 10, 1821. He invited participants on a trip “to the westward for the purpose of trading for Horses & Mules, and catching Wild Animals of every description, that we may think advantageous.”

Several months later, Becknell led five other men from Franklin, Missouri and crossed the Missouri River at Arrow Rock, then headed to the southwest. A short time later, Becknell’s party learned of Mexican Independence from Spain and the lifting of trade restrictions. With Becknell’s arrival in Santa Fe on November 16, 1821, the first legal commerce with New Mexico took place. Followed by other trips, now with wagons loaded with trade goods, William Becknell became known as the “Father of the Santa Fe Trail” between Missouri and New Mexico. This set in motion over a half a century of commerce and cultural exchange between New Mexico and eastern trade centers.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed in 1848, ended the war between the United States and Mexico. By its terms, Mexico ceded 55 percent of its territory, including parts of present-day Arizona, California, New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah, to the United States. For more information about the Mexican War from the perspective of First Lieutenant Isaac Bowen, a United States military officer, refer to Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters, Part One, for his detailed description of deployment to Northern Mexico, two intense battles during the Mexican War (1846-1848), and the boredom of occupation.

Which Way to Go?

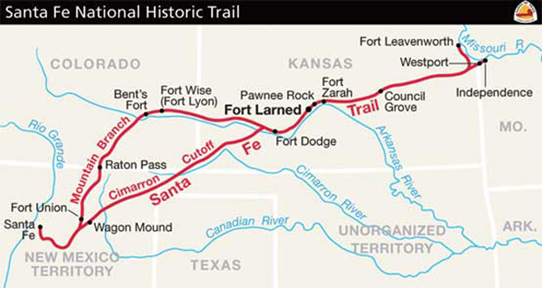

Travelers on the Santa Fe Trail had the option of two different routes: The Cimarron Route or the Mountain Route. Either way, they had to be prepared to carry wood and water. Captain Isaac Bowen’s party ultimately chose the Mountain Route the summer of 1851 on their way to the newly established Fort Union, New Mexico Territory.

“Isaac has a chart with all the camping places put down and marked with or without wood and water, as the case may be, and of course where there is none, we will carry from the last place. I do not anticipate any difficulty in the want of wood and water.” Katie Bowen on the Santa Fe Trail, June 1851

“There is not a sprout to be seen anywhere within 5 miles and we brought our wood from Diamond Spring, 19 miles back. Here at Cottonwood, we have a great abundance of wood and water and must carry wood from here to last us 60 miles, allowing for long marches in case of bad traveling.” Katie Bowen on the Santa Fe Trail, later in June 1851

After the Mexican War, military traffic joined commercial traffic along the Santa Fe Trail. The Cimarron Route was the most commonly used route to and from Santa Fe in the earliest days of the Santa Fe Trail, even though the path was known for its scarcity of water. This route was shorter by about 100 miles and was more suited to wagon travel. With poor grass and scant water, the sandy Cimarron River, which was often dry, defined the landscape as one of the riskiest sections of the entire Trail.

Over time, as more and more people encroached upon Indian territory, many Santa Fe traders and military wagon trains began taking a second look at the Mountain Route of the Santa Fe Trail.

Though the Mountain Route of the Santa Fe Trail presented some problems, especially the crossing over Raton Pass, it most definitely had its advantages, including the fact that it had plenty of water and was relatively safe from Indian attacks. Although longer than the Cimarron Route, it became the favored route at various times due to drought and hostile Indian raids along the Cimarron Cutoff.

The Mountain Route made its way into Colorado, passing by the site of Bent’s Fort before making its way along the treacherous, steep and unforgiving Raton Pass. Through here, wagons often had to be dismantled and hoisted over rocks and ledges, a process that could add days to the trip to Santa Fe. Early travelers observed broken remnants of wagons strewn all along the way over Raton Pass.

For first-hand descriptions of the Bowens’ first trip across the Santa Fe Trail, read Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters (Part Three: The Santa Fe Trail), including Katie Bowen’s descriptions of crossing the Raton Pass on foot, while pregnant.

“On August 14, we came over one hill three quarters of a mile up and the same down, and of all the places we read of, judge. We made three miles in three hours. It was formed of loose large round stones, or rather rocks, piled up like stairs and such a getting upstairs and down again, no mortal but those who cross Raton Mountains can conceive. Each individual rock rolled with the wheels, which sent the wagons dancing on nothing. I rode up, but could not bring my mind to ride down, so away I footed it over rocks, bushes, briars and all, but got to the bottom at last.” Katie Bowen crossing the Raton Mountain, August 1851

The route of the Mountain Branch follows present-day I-25 over Raton Pass and parallels Highway 64 to Cimarron, New Mexico. The two routes converged near the modern town of Watrous, New Mexico, and the complex of Fort Union. It then continued through several Hispanic settlements and the historic ruins of Pecos Pueblo before it emerged from the passes of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and into the Santa Fe Plaza.

Regardless of which path the travelers chose, they faced many hardships along the Santa Fe Trail. The caravans could not escape the harsh Plains, desert, and mountain elements along the 900-mile trek. These included dry spells, torrential rains, huge lightning storms, wolves, rattlesnakes, fires, and stampeding bison herds. Summers were very hot and dry, and the winters were often long and bitterly cold. Lack of food and water also made the trail very risky.

River crossings were particularly troublesome. Although shallow, Plains rivers were filled with sinkholes, quicksand, and other hazards that required careful maneuvering. In Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters, Katie Bowen captured all of this in Part Three: The Santa Fe Trail, in her journal entries.

“Last night we camped at “Soldier Creek” where the ox wagons were crossing nearly all day. One of the soldiers who had been hard at work all day went in to bathe at night and got into a deep hole where he went down and came up no more. His comrades immediately went in after him, but could not find him, and although they watched nearly all night and dragged the stream in several places, they had to leave this morning without finding him to bury.” Katie Bowen on the Santa Fe Trail, June 1851

In Lifelines – The Bowen Love Letters, Captain Isaac Bowen and his wife, Catherine “Katie” Cary Bowen, traveled on the Santa Fe Trail for three months. They left their staging point at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in June 1851 and arrived at Fort Union, New Mexico Territory, in August 1851.

“My dear Mother, at last we are at our destination, safe in every particular, in health and our goods in as good order as anything could possibly be after the hard journey they have had. I for one have not found the trip at all annoying. The time did not seem long, for everything was pleasant, weather and country. This point is 100 miles nearer home than Santa Fe, located particularly with a view to the extensive farming operations, and certainly it is well adapted – plenty of water, abundance of wood – and to all appearances a fertile valley with mountains on two sides of us. The hills are close by and timbered with pine, red or pitch pine I believe – anyway it makes good lumber and fine wood and will not fail a supply in a thousand years.”

This is Katie Bowen’s first letter from Fort Union, New Mexico Territory, to her mother in Houlton, Maine. After reading all of her letters and journal entries along the journey, it doesn’t ring true to me. I think Katie told her mother what Catherine Cary wanted to hear, reassuring her that Katie didn’t find the three-month trip across the Santa Fe Trail in 1851 any hardship and that everything was pleasant, including the weather. That was not the case!

Does the Santa Fe Trail matter, 200 years later? I believe that it does because it connected the more settled parts of the United States to the new southwest territories. Commercial freighting along the Trail boomed, including considerable military freight hauling supplies to the southwestern forts – to Fort Union first, as the supply depot where Captain Isaac Bowen served as the first Chief of Commissary for the New Mexico Territory. The Trail was also used by stagecoach lines, mail service, adventurers, missionaries, wealthy Mexican and New Mexican families who sent their children to St. Louis, Missouri, for higher education, and of course, emigrants.

By the early 1870s, however, three different railroads vied to build rails over the Raton Pass in order to serve the burgeoning New Mexico market. The winner of that competition, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, reached the top of Raton Pass in late 1878. Additional track mileage further shortened the effective distance of the Santa Fe. Then, in February 1880, the railroad reached Santa Fe, and the Santa Fe Trail faded into history.